|

|

|

|

The first fully automatic digital computer that could be programmed was

developed by

Konrad Zuse in Berlin during World War II. A description of the

years of intense work under very difficult conditions is found in Zuse’s book

appropriately

entitled "Der Computer - Mein Lebenswerk." 11 The first

working model was the Z3 introduced in May 1941. It was based on

electromagnetic relays: 600 relays in the computing unit and 1400 in the

storage unit.

It used a binary number system, floating point operation, 22 bit word length and

had a storage capacity of 64 words. It required a special keyboard to generate

the input via an 8-channel punched tape (i.e., one instruction represented by

8 bits).

Most parts of the computer were constructed from used materials because new materials were hardly available during the war. This meant, for example, that the various relays required different voltage, and this had to be considered also. Nevertheless, the machine was apparently relatively stable in its performance. The speed was about 3 seconds for multiplication, division, or taking a square root. The Z3 was used to calculate determinants and, in particular, complex matrices that were important in optimizing the design of airplane wings. Part of the work on the Z3 was financially supported by the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt. This first model was completely destroyed in 1944 by Allied bombs, but a replica was reconstructed 1960 and can be seen in the Deutsches Museum in München. |

Photo, © and more info here. |

Work continued for a while in the building of

the Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt in Göttingen, which is near the center of

Germany. From Göttingen, Zuse and some of his friends escaped in 1945 with

the Z4 to Hinterstein, a small village close to Hindelang in the German Alps

where other scientists such as Wernher von Braun had also found some shelter.

In these years, they were entirely isolated from the rest of the world and heard

only after the war the details of computer developments in the United States

(MARK I, in operation 1944, and ENIAC, operating somewhat later) and in

Britain (COLOSSUS, which was a stored program machine to break the code

of the German forces in the war). There was no possibility of continuing work

on the Z4 until the monetary reform of 1948. Zuse in Germany had been the

first with an operational freely programmable digital computer but had lost

the competition with other countries due to the war situation in Germany.

|

more here Photo and © Univ. Penn State |

Zuse Z22 - Photo and © from here. |

Zuse Z23 - Photo and © from here, where there is more to be found on Zuse |

born 1914 Photo and © Max-Planck-Gesellschaft |

Late in 1947 the building of the Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt in Göttingen, which had housed the ZUSE Z4 for a short time during the war, became available for new institutions and institutes, including the Kaiser- Wilhelm-Gesellschaft (today called the Max Planck Gesellschaft) with Max Planck and Otto Hahn, and the Institute of Physics with Werner Heisenberg, Max von Laue, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. The experimental groups had to construct equipment since nearly all laboratory equipment had been destroyed in the war. Heinz Billing 12 started to build a small High-Frequency Lab in the "Institut für Instrumentenkunde" with a few instruments to measure electric currents and with some vacuum tubes left over from the German army. He was fascinated by a very short note on the existence of the ENIAC computer in the United States, a computer containing 18,000 vacuum tubes and with a weight of 30 tons. |

Photo and © here. |

|

Billing’s development work was interrupted by the monetary reform of

1948, which caused heavy cuts in the Institute’s budget. Billing’s engineers

took job offers from Argentina, and he himself accepted an offer from

Australia in order to develop a computer including his magnetic drum

at the University of Sydney.

He left a detailed description of the design of his computer in

Göttingen, however. Since the astrophysicist Ludwig Biermann

in Göttingen was extremely interested in numerical calculations and

believed in the future

of digital computers, he convinced Heisenberg to bring Billing back. In June

1950, Billing was back in Göttingen and started to work on the computer,

and Heisenberg was even able to obtain funds from the Marshall Plan to

buy vaccum tubes and resistors. |

Ludwig F.B. Biermann 1907 - 1986 Photo, © and further Bio here. |

Photo and © from here. |

|

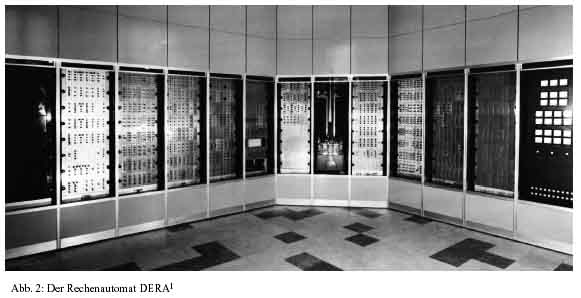

In the 1950s, the design of computers also started at various German universities. These efforts were supported by the German Science Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG), which initiated a special committee for this purpose (Kommission für Rechenanlagen). Main competitors to the machine in Göttingen were Professor Walther with Hans-Joachim Dreyer at the TH Darmstadt whose DERA machine went in operation in 1957, Robert Piloty at the Technical University (TU) of München with the PERM (1956), and Friedrich Willers with Joachim Lehmann in Dresden with D1 (1956) and D2 (1957). |

1898-1967 |

|

Even though PERM stands for "Programmgesteuerte Elektronische Rechenmaschine München," some people called it "Piloty’s erstes Rechen-Monster". {website:P.'s first monster calculator} This computer was later put under the guidance of Professor Friedrich L. Bauer at the TU München. More information can be found in Refs. 12 and 13. Looking back at these early developments at a research institution in Göttingen and at several universities, it is regrettable that the German industry was not able to take advantage of this knowledge and lost out in the internationally fast growing competition in computer technology. |

The rackheight was about 3 meters. |

Hans Kuhn at the University of Marburg was interested in the spectra of dyes 14. Based on the electron gas model, he could understand the quantum mechanical states involved in such light absorption processes in a qualitative way, but he wanted to have quantitative results. So he developed an analog computer to determine stationary wave functions and corresponding energies of a particle (it electron) in a one- and two-dimensional (1D and 2D) potential field as given by the Schrödinger equation. The basic idea was put forth 15 in 1951 when he experimentally determined the vibrational frequencies of membranes whose form represented that of certain (planar) molecules. The transition from the mechanical system described by masses and springs to the analogous electrical system replaces masses by self-induction (coils) and springs by capacitances. The potential acting on the site of an atom could be changed by an adjustable capacitor. The entire network was driven by high-frequency voltage that was varied to obtain stationary electric waves. Hence, the actual computer was based on the analogy between oscillatory states of a network of electric circuits and the stationary waves of a corresponding quantum mechanical system. |

The energies of the stationary states

were given by the applied frequencies and the corresponding wave functions

by the voltage at each mesh point of the network. The entire network had

4000 resonators; a picture of the size of the installation can be found in

Ref. 16 and details to the installation in Ref. 17. |

Photo and © ref 17. |

Kopineck based some of this work on

the tables of auxiliary functions published in 1938 by Kotany, Ameniya,

and Simose 22, but was careful enough to recalculate all those that he

specifically needed and found that the Japanese tables were very reliable. Apparently,

these latter tables had been overlooked when other work started on the

evaluation of integrals for selected applications 23.

In Kopineck’s papers, 21, 24, 25,

acknowledgment is expressed to Professor K. Wirtz for suggesting the work,

to Professor L. Biermann for support, and to a group of people of the

astrophysical section of the institute (director Biermann) for carrying out all the

tedious numerical computations. This happened all before the electronic

computer G1 became available. A very interesting work on the potential energy

curve of N2 as a 6- and 10-electron problem based on the Heitler-London

method as described by Hellmann 20 made use of the previous tables of

integrals and is among the first German publications in this area. This 1952

paper was dedicated to the 50th birthday of Heisenberg. |

|

Photo and © here, where some additional CV may be found. |

In 1952, Heinzwerner Preuß came to the Institute in Göttingen as successor to Kopineck. He already had experience in H2 calculations and integral

approximations 29 performed while at Hamburg, and was the ideal person to

continue the work on integral evaluation in Göttingen. He first extended the

studies to heteronuclear diatomics, and later on, with the use of the G1 and G2

electronic computers, this work culminated in four books Integraltafeln

zur Quantenchemie. 30 These volumes give an excellent introduction to

the general problem of quantum chemical calculations and contain many

references to historical work in this connection. They are also an excellent

dictionary to look up details of the analytical derivations of molecular

two-center integrals over Slater functions and their necessary auxiliary

functions. The numerical values are tabulated for a small grid so that intermediate

values could easily be obtained by interpolation. These tables were used for

quantum chemical calculations 31 of diatomics until the beginning of the

1960s. I used these tables of Preuß for the first part of my doctoral work. The computation of integrals for a valence bond treatment of the H-F molecule on a mechanical desk calculator was greatly simplified by the fact that I could look up values for the required auxiliary functions in these tables. Toward the end of this work (1962-1963), I got access to the electronic computer Z23, which of course could perform the calculations in a much shorter time with much higher accuracy. |